By Jon Seaman

For an endurance athlete, “Did Not Finish” or the three painful letters “DNF”, hides stories of catastrophic failure. Crashes, injuries, illness, lack of fortitude, lack of preparedness, freak weather, broken equipment, faulty navigation, and missed time cuts—are just some of the endless reasons why we fail.

We are trained through a common narrative reinforced by news, movies, books, social posts that no matter what challenge you face, you can overcome it with the sheer force of your will. Any other outcome is just an excuse that a loser makes.

In our 'we are the champions, no time for losers' society, is there room for public failure? Does context matter? Can we learn anything from careful introspection and a detailed examination of our mistakes, or are we just rationalizing to salve the pain?

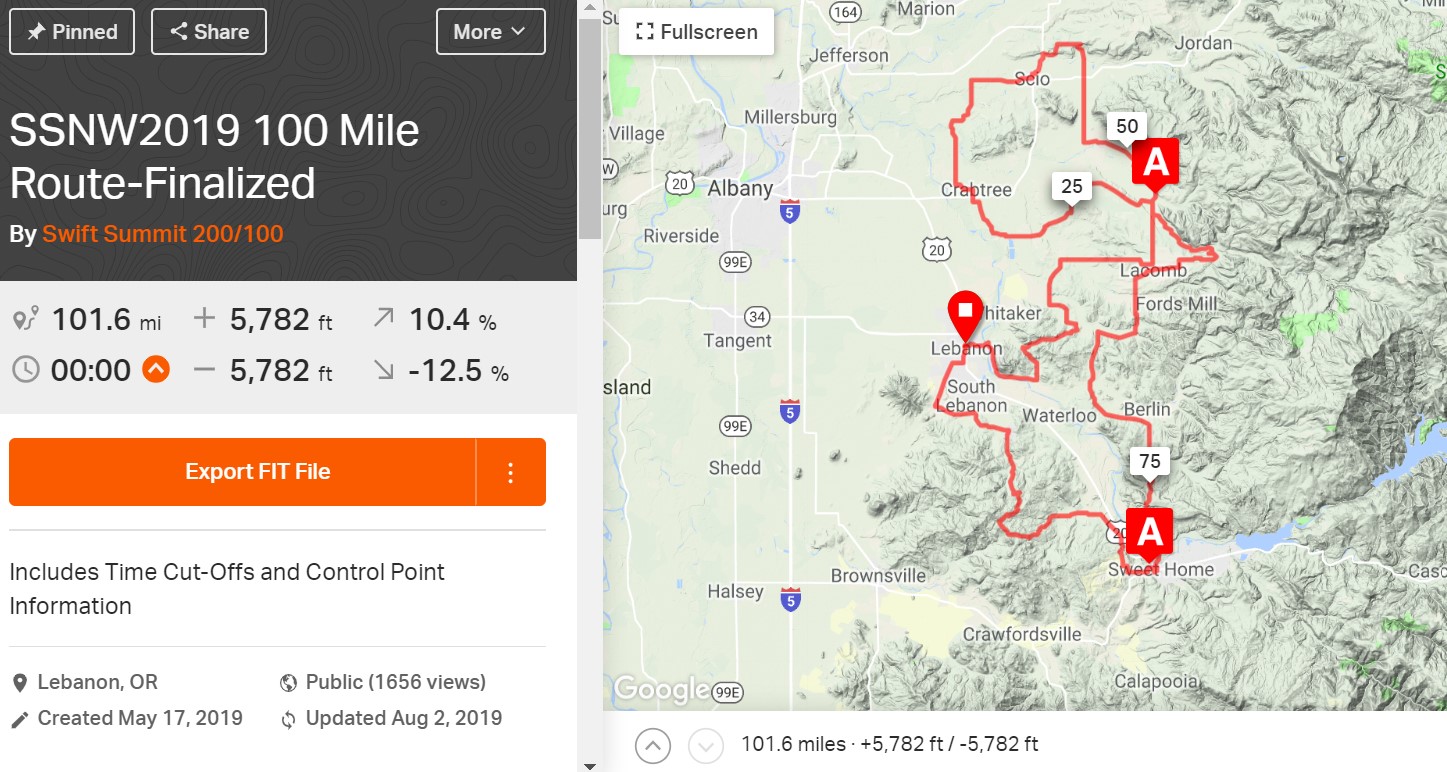

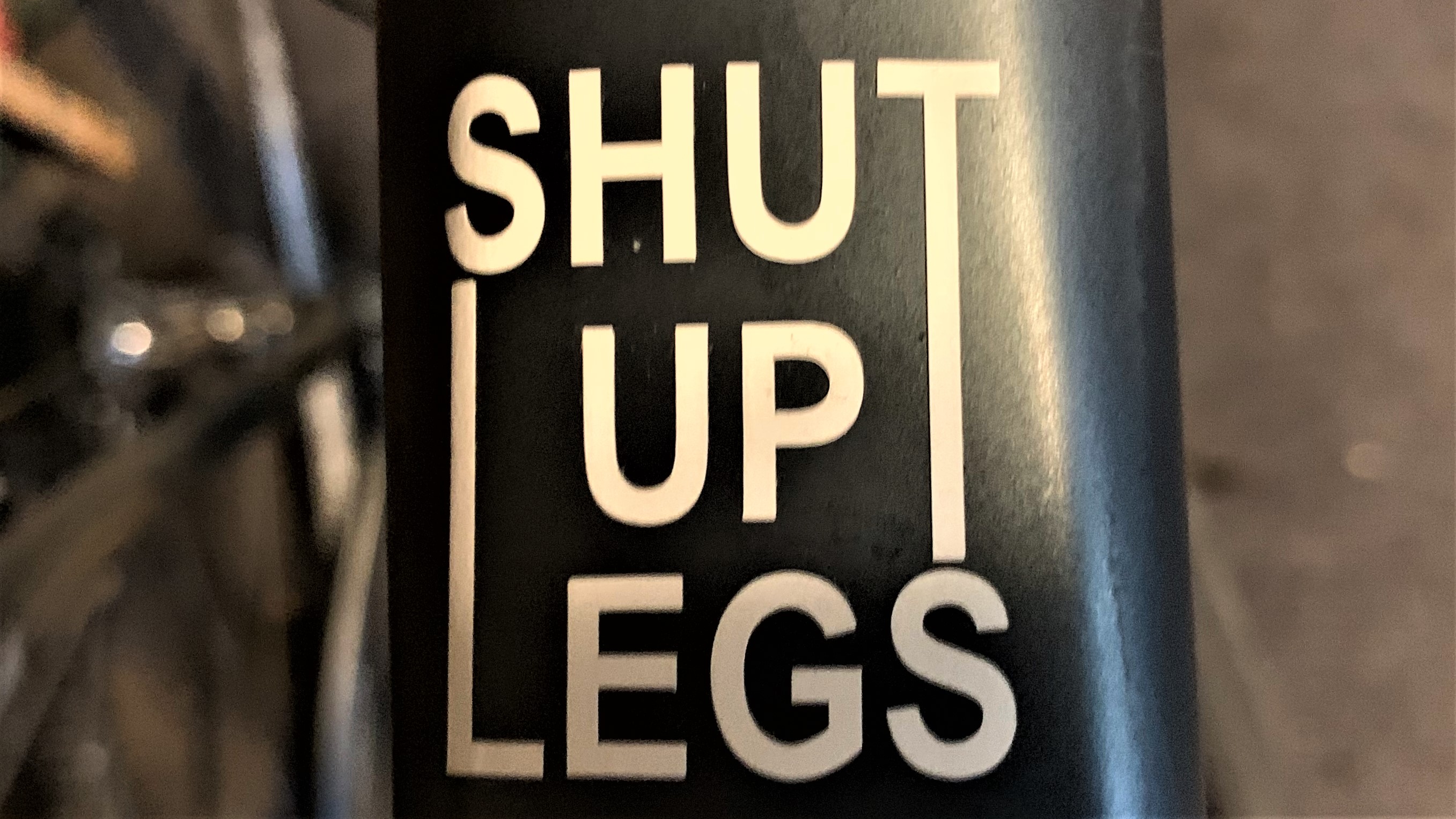

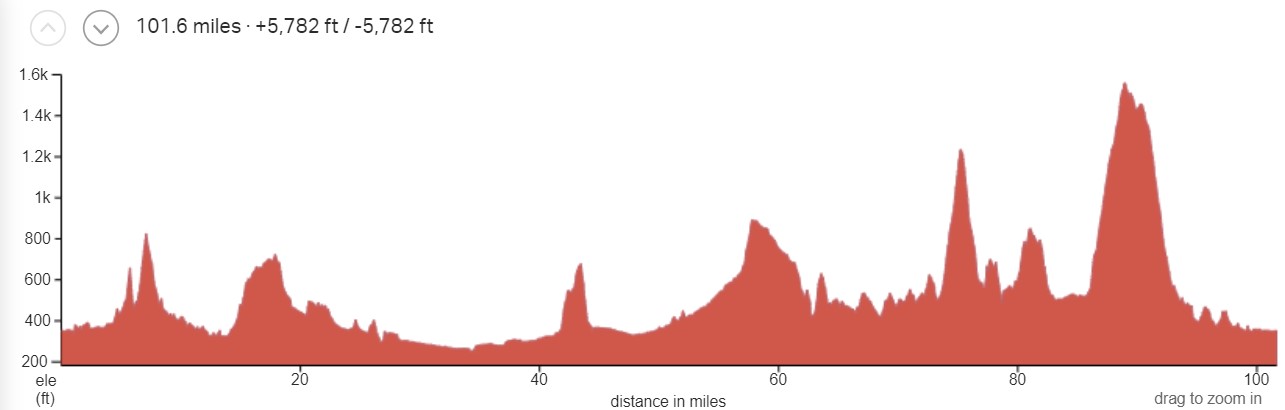

A few weeks ago, I rode in the Swift Summit 200/100. This was a very challenging event. It was a self-supported, Gran Fondo style race. I rode the 100 version which was 101.6 miles with 5800 feet of climbing. There were only two checkpoints/aide stations. One at 50 miles and one at 80 miles. Mostly they were used to time stamp control cards and enforce cut off times. This event is a step-up in difficulty from a normal charity century. I was eager to take it on.

I won’t keep you in suspense. I did not finish. I DNF’d. I managed to make it through 92.5 miles and 5248 feet of climbing. I was 9 miles from completing the event when I called for the support vehicle and took the free ride of shame to the finish line.

What did it mean for me that I DNF’d? I did not get to roll through the finish line at Conversion Brewing. I received no cheers from the celebrating crowd. I didn’t enjoy a high-five and hug from event organizer and friend Trevor Spangle. I did not get to sign my name on the banner of finishers. I did not get a tasty Swift Summit-branded IPA and beautiful personal pizza that I had been dreaming about for the last 8 hours. I didn’t hang out and listen to the rowdy rock band that underscored the finishing riders. I didn’t get to do the “look what I did, humble brag” Facebook and Strava posts. I didn’t get to celebrate and swap victory stories with my friend and personal hero, Dave Anolik, who rode and finished the even harder 200-mile version.

***

***

Here's Dave at the finish line being greeted by Trevor

No, I was dropped off in front of the venue where my wife waited anxiously with my dog. My wife had been expecting me three hours earlier. She had been in a near panic and having a running dialog with event organizers to get updates on my status. I gave my wife a weary hug. I scratched my dog behind the ears. I apologized profusely. Then I sidled shame-faced through the back of a boisterous crowd to pick up my drop bag. I loaded my bike up on my car and my wife drove us the 90 miles home while I fought off leg cramps.

By any objective measure, I failed. I did not finish. No excuses. It was painful, humiliating, and made more embarrassing because I work for VeloPro, a training company that’s sole business is to prepare cyclist for endurance events. How could this happen?

That’s it. If you are a champion with no time for losers, you can stop reading right here and go on with your glorious life. Story over. For anyone else who has experienced a disappointing failure, please hang around a bit. There’s more context to this story. Let’s see if there is any value in viewing the world in color instead of black and white.

It has taken me weeks to process the experience of the Swift Summit. I was challenged beyond my expectations. I was pushed to my physical and mental limits. My confidence was rocked. I’ve lost perspective, I’ve gained perspective. I’ve been confused, angry, grateful, giddy and plagued by dreams that replay moments from the ride.

Context Reveal #1: Failure.

This is not the first time I have failed to finish the Swift Summit. In my first attempt last year, I had a tachycardic event on the first big hill 5 miles into the ride. My heart raced to over 215 beats a minute and did not recover for 20 minutes. I had never experienced this before in my life. I was beside myself and terrified, but I refused to quit. I continued to ride until I reached the first checkpoint at mile 46 and they then took me to the emergency room. If you want the whole story for that epic adventure, you can read more about my insane ride here in my “letter of encouragement to a Swift Summit rider."

In this new context, the 92.5 miles I rode in this year’s Swift Summit was double what I achieved last year. As an added bonus, no emergency room visit!

Context Reveal #2: Training.

I was in the best shape of my life for this year’s Swift Summit. This is not hyperbole. I have the data to prove it. I had been training for this event for six months. I was determined to get revenge for last year's failure. I had a complete training plan. I prepared with regular training rides enhanced by other cycling events, and occasional group rides. I finished the Mohawk Metric Century and Strawberry Century without difficulty and set new personal bests.

Here's support list that I taped to my bars to make sure I was on schedule.

I also went the extra mile in my Swift Summit preparations. I created performance support tools to tell me when I needed to eat, hydrate and prepare for the big hills. I reviewed the route many times. I carried extra hydration. I trained with a Camelbak backpack with extra water, food and bike tools to prepare. I changed from my racing bike to my gravel bike, so I had proper gearing for tough hills. It was not enough. The cool and rainy conditions caused my prescription cycling glasses to fog up. I had never had this problem before. Not being able to see is scary, especially on descents. The more troubling thing is that The Mark’s Hill Winery and Mountain Home Climbs were absolutely beyond my capability. It wasn’t just a case of “shut up legs.” My legs didn’t hurt, they were dead and non-responsive. I had never felt this before. I literally hiked my bike up those hills cyclocross style. Humiliating!

In this context, I needed to do an analysis of where my training went flat. I struggled greatly on the two brutal hills at the end of the race. I just couldn’t generate the power needed to climb for several miles at an average of a 9%+grade (450+ watts for 20-40 minutes). In my training rides, I did not face hills as difficult as the two major climbs I faced at the end of the Swift Summit. It was the combination of grade and length that pushed me beyond my limits.

Context Reveal #3: Health.

I am not a typical or lifelong athlete. I am 52 years old, 6’6” tall and weigh 225 pounds. I am what cyclists derogatively call “a Clydesdale.” The hills are not my friend (see above). Also, I have only been riding seriously for 3 years. Why only 3 years? I am a kidney transplant recipient who has battled kidney disease my whole life. For most of my adult life, it was all I could do to walk up and down a flight of stairs. I spent years on dialysis before receiving a kidney from an anonymous living door. It was the equivalent of winning the lottery and it saved my life. I still take tons of immune suppressing medications and have very odd complications. I am continuously monitored by doctors. I take unique precautions to ensure I am properly hydrated and don’t do anything to damage my donated kidney. Because the event checkpoints were so far apart, I carried 9 liters of extra water! The extra water, food and weight of my bike put my total weigh at 275 pounds. Too much! I overdid it.

In this context, the fact that I am well enough to ride regularly and well is astonishing. It is the greatest luxury to often forget I’m not a normal cyclist that is half my age. However, I do need to set ambitious but realistic goals. The expectations I had for my performance may have exceeded my capabilities.

***

***

Context Reveal #4: Safety.

Andrew “Bernie” Bernstein. “Bernie” is our VeloPro account manager at True Communications. True helps VeloPro with PR, social media and business development. Two weeks before the Swift Summit, Bernie was cycling home from training at a cycling track in Colorado when he was hit from behind and left for dead by the side of the road. It was a national news story. He was on a ventilator in critical care when I rode the Swift Summit. Honestly, he was never far from my thoughts. It is a harsh reality that, as cyclists, we are exquisitely vulnerable.

Trevor Spangle, the event director, revealed to us right before the rolling start that while most of the local community was supportive of the Swift Summit, there was a tiny minority who were angry. In fact, a couple of people threatened on social media to shoot or run over cyclists participating in the event. These people were reported to police and monitored, but still it was very troubling.

Due to my slow riding speed (13.5 MPH) and a critical navigation error that took me 5 miles off course and well behind the pack, I rode 90 of my 92.5 miles alone. I rarely saw other riders except at the checkpoints. It was unnerving.

I do ride with front and rear lights that have cameras built in (Cycliq brand). In case anything goes wrong, it will be captured! The ride started off with heavy clouds and rain, so I turned on my lights and cameras. I never anticipated I would be on the road for more than 8 hours! My cameras and bike lights ran out of power five hours into the ride. Not exactly a safe situation.

In this context, it is important to be safe. I should have been prepared with battery backup! It is even more important to have the support of fellow riders and riding companions. I doubt I would have made such a terrible navigation error if I was riding with companions. Going it alone makes the task more difficult. I only had the demons in my head for company.

Content Reveal #5: Why I Quit.

Riding alone and relying on myself without any help was my plan. In retrospect, this was obviously a short-sighted mistake. I made critical unforced errors by not having any help. Yes, I was slow. Yes, I made a bad navigational error. Yes, my legs were dead toward the end of the race and I had to push my bike up the last two nasty hills. I was even the last rider to arrive at both checkpoints. However, I still made it BEFORE the official cut-off times. I did not quit when probed by the support staff if I wanted to continue.

My abused and rain-soaked control card.

I had the opportunity to quit 1000 times along the ride. Truthfully, my mind was a raging battle. I constantly questioned why I was putting myself through the misery and suffering. My mind relentlessly searched for reasons to quit. I said horrible things to myself. I questioned my resolve, my value as human, my will and my intelligence. I terrorized myself with thoughts of letting down VeloPro and our My First Century cycling team.

To combat the mental onslaught, I recited the lines to a poem called “Self-talk” that I wrote when I was on dialysis and was fighting for my life. You can read it at the end of this blog. As motivation to ride on, I used the fantasy of being awarded the “Lantern Rouge” award (last to finish) by Trevor Spangle at the finish line. I tricked myself to go a little bit farther by committing to make it “just to the next” highway sign, mailbox, or mile-marker.

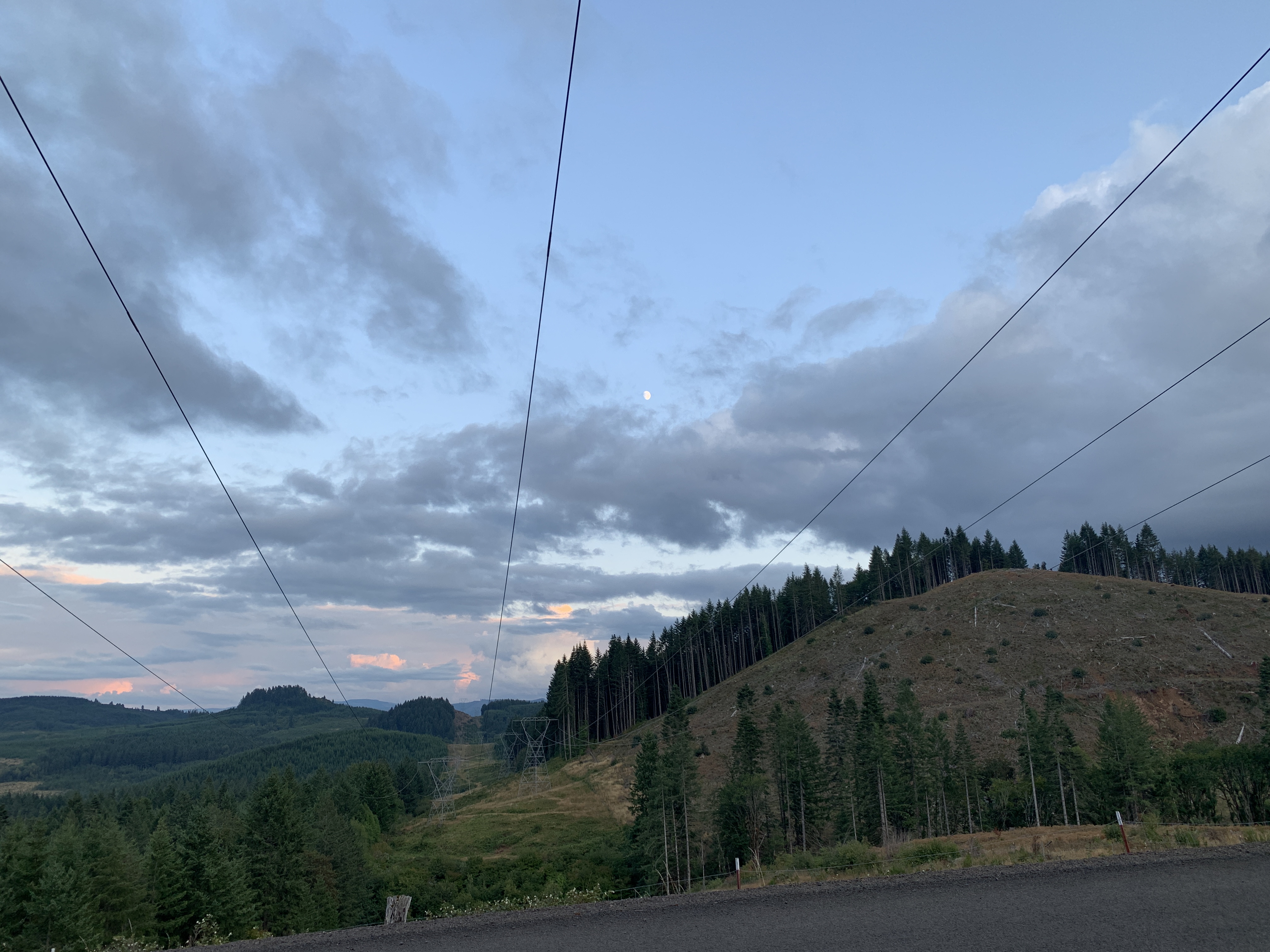

The truth is that I could have finished! I was on the last climb hiking the bike at a painfully slow crawl. I was jelly, alone, completely out of gas, but I was nearly at the summit. I anticipated a long and speedy descent into the last 10 miles to the finish line. I just ran out of time. The sun literally set on me. I had no lights and no battery backup. To descend in the dark at 40 MPH would have been suicide. Not only could I not see anything, cars could not see me. I thought of Bernie.

Was I willing to die to reach my goal? The answer was, “No.” When I realized that I wasn’t willing to die, this is the moment I quit. It wasn’t fair to my wife. It wasn’t fair to Swift Summit and other successful riders.

In this context, I am certain that I did the right thing. Still, I feel like failure. My mind continues to dwell on the mistakes I made and flashback to moments of the ride.

This is the moment I quit.

Context Reveal #6. Surprise!

To make sure I’m not endangering my gift kidney, I always follow up after an endurance event with bloodwork and a visit to my doctor. My last visit was in Jun,e right after the Strawberry Century. I was ecstatic that my lab results were perfect, no detrimental effects. However, this time was different. My doctor revealed to me that I was severely anemic and had extremely low levels of iron. This meant that during my Swift Summit ride, I was lacking oxygen carrying red blood cells to power my muscles. I was only riding at 50% capacity. My doctor was surprised that I didn’t end up in the emergency room again. Now I am scheduled to receive iron infusions. I will also need new tests to figure out why my numbers are so low. I am both relieved there was a reason for my difficulty at the Swift Summit and completely frustrated. The journey continues.

Conclusion:

Context does matter. Color adds life and meaning to the story. While I did not finish the Swift Summit, I am not a failure. I doubled my performance from last year! I faced new and unexpected challenges, but I did not wilt. I fought on. With a few minor changes and some help from friends, I can do this. I will give the Swift Summit try number 3. I will not quit. I also realize that I need to lighten up. I am not nor will ever be a professional athlete. The stakes are selfish. Finishing the Swift Summit is a goal for personal growth. I am very, very lucky to have a loving and supportive wife and a beautiful dog. Finally, the most painful letters are not DNF. They are DNS, Did Not Start.

My wife and dog.

***These asterisks indicate the picture is by Harry Apelbaum the official photographer of the Swift Summit.

*“Self-talk” was the first-place winner of the Portland Pen Award and was published in Spring of 2010.

Self-talk

By Jon Seaman.

Unfold yourself

from the origami of your rage.

Those newspaper-bruises

and brittle flakes of soy ink scorch,

but will dissolve

in acid rain of memory.

This need not be your obituary.

Unearth yourself

from memoir remains.

This fading papyrus, this codex,

this evidence of sad scribal skills

is not in language lost. Your name

not signed in blood. This need not be

your final testament.

Unleash yourself

from this steel maw snare

of savage fear-bite faith.

Unknowable questions that with wolf-teeth

gnaw and rend and tirelessly tear.

You need not strangle

on a choke-chain life.

Unhinge your jaws

and devour yourself whole.

Your vision and venom

is no longer lethal. Today, old serpent,

you are a patient snake,

a time constrictor.

This is not your final meal.